App Updates

Today I work as an SRE, surrounded by dozens of complex systems designed to make the process of taking code we write and exposing it to customers. It's easy to forget that software deployment itself is a problem that many developers have not yet solved.

Today I'd like to run you through a straightforward process I recently implemented for Git Tool to enable automated updates with minimal fuss. It's straightforward, easy to implement and works without any fancy tooling.

Background

Let's consider a simple application which is composed of a single executable. While your specific application might be more complex, this use case allows us to focus on all of the interesting problems related to updates without over-complicating the discussion.

Our application will need to (either on a schedule, an event or at the request of a user) look for an available update. The exact protocol you use to accomplish this is up to you and doesn't need to be complicated; I discuss this further in the Checking for Updates section. Once you've identified an update, the goal will be to replace your application's executable with the updated one "in place".

This is a bit trickier than it sounds because many modern applications hold a read handle open on their executable and this makes unlinking the file (deleting it) impossible while the application is running. The three phase update solves this by having the application shutdown to facilitate the update, however that also removes your ability to keep executing code to orchestrate the update...

Three Phase Updates

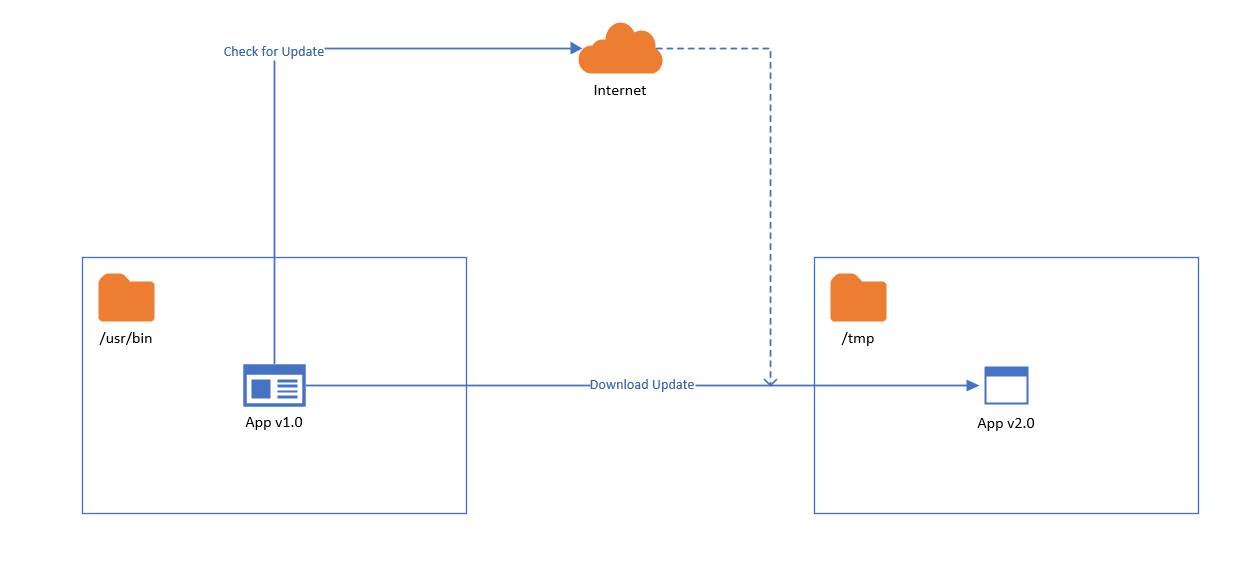

Preparation

The first phase of an update involves preparing the system to receive the update. Generally this involves downloading the necessary artifacts onto the machine (usually in a temporary location) and ensuring that all work is saved. In certain conditions you may wish to backup the current working version to support a rollback operation, or you may use this chance to ensure your data has been migrated to a format supported by both the current application version and the new update.

Once the preparation phase has been completed and the application is ready to be updated, it will launch a copy of itself (usually the downloaded update instance) and instruct it to run the second phase. The second phase will not be able to proceed while the first application is running, so it will then terminate to release any locks it holds.

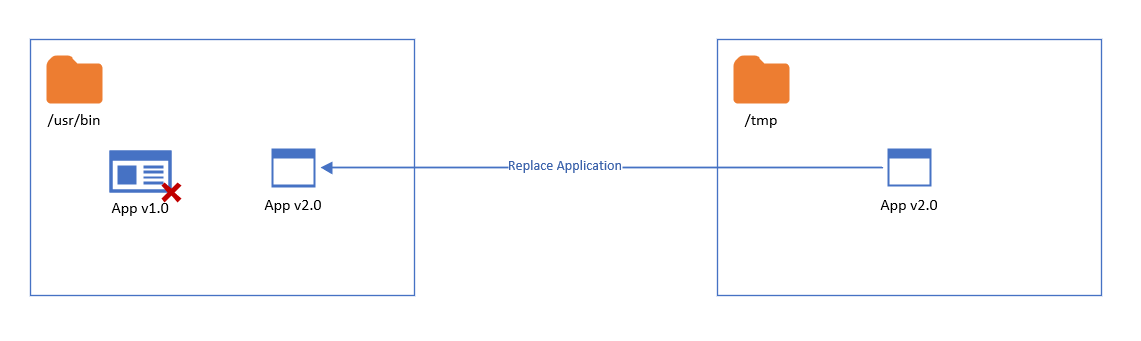

Replacement

The second application to be launched, usually the downloaded update artifact itself, is instructed to run the second phase of an update. This phase involves removing the old application and copying the update artifacts into its place. While not strictly necessary to use the update application for this purpose (you can have a dedicated updater), this approach does allow you to quickly start running the latest update code-paths and can help you address bugs in the update process which would otherwise require human intervention.

Once the application has copied the latest artifacts into place, replacing the old application version, it will start a third application instance (generally the newly updated application) and instruct it to commence the cleanup phase. Again, the cleanup phase will not be able to proceed while this replacement application is running if the replacement application holds locks on any of the temporary update files, so it will need to exit.

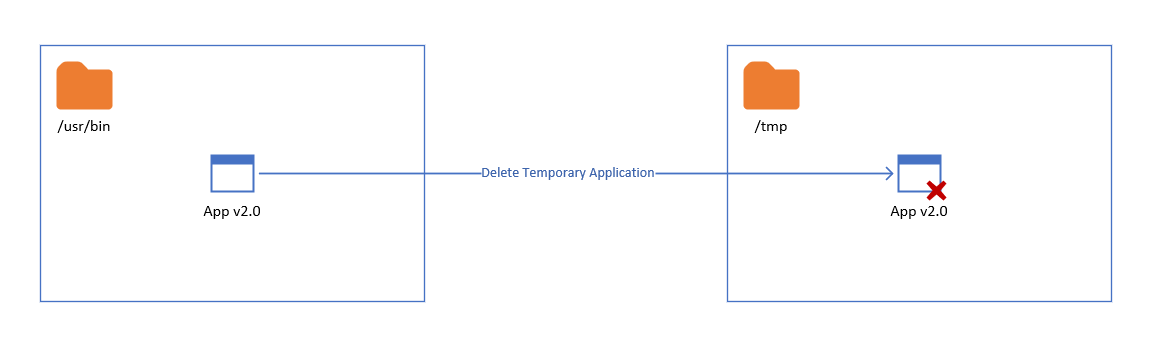

Cleanup

Finally, the cleanup phase involves the application removing any temporary files associated with the update. Usually this means removing the temporary copy of the update which was used to perform the replacement, however you may also remove any rollback artifacts if they are no longer needed.

At this point the application has been updated and depending on your use case you can either exit or continue running from where the user left off.

Checking for Updates

Checking for an available update can take many forms depending on how you publish your artifacts, what services you use to manage builds and how your application works internally. For the most part, the simplest solution is to use an HTTP request to query a known endpoint for a list of new versions.

This endpoint can either be served dynamically, or it can be a static file hosted on your content delivery network. Each has its own benefits and if you need the ability to feature-flag updates, perform phased roll-outs or control access to versions then you'll probably want to build an API to expose this information. For the rest of us, a basic JSON/XML file will do the trick.

The important part is that you are able to determine whether an update is available, which version of the software it represents and where to download the update itself.

GitHub Releases

I personally like the idea of using GitHub Releases to manage my updates. They enable me to quickly and easily publish/un-publish updates; tightly integrate into my normal release workflow and have great support for release notes. Not only that, but they also allow me to publish multiple artifacts (supporting different platforms, for example) as part of a single release.

To take advantage of this, I simply have my applications consume the GitHub Releases API and compare their internal version number against the SemVer tag names I use. When they find a new release they have immediate access to the list of relevant artifacts and these are served by GitHub's global CDN; making them blazingly fast to download.

GET /repos/:owner/:repo/releases HTTP/1.1

Host: https://api.github.com

Accept: application/json

update-go

All this is great, but it'd be nicer if you didn't have to write it all in the first place right? Fortunately I feel the same way, so I've put together a Go library in the form of update-go which lets you do this all with hardly any effort at all on your part. This library offers a number of nice features to build your own three phase update implementation as well as a high-level Manager which will take care of the entire process for you. I've included some code below which demonstrates how one would use it.

package main

import (

"os"

"log"

"path/filepath"

"context"

"time"

"github.com/SierraSoftworks/update-go"

)

// Update this on each new release (ideally using the "-X main.version=1.1.7" compiler flag)

var version = "1.0.0"

func main() {

mgr := update.Manager{

// What application are we updating?

Application: os.Args[0],

// Provide a path where the update file will be stored temporarily

UpgradeApplication: filepath.Join(os.TempDir(), filepath.Base(os.Args[0])),

// This encapsulates the platform and architecture you're running on (linux-amd64 etc.)

Variant: update.MyPlatform(),

// Make sure you fill in your :owner/:repo here as well as any prefixes for your

// release tags (in my case vX.Y.Z) and artifacts (myapp-linux-amd64).

Source: update.NewGitHubSource(":owner/:repo", "v", "myapp-"),

}

// We use a context to ensure that the update doesn't hang permanently, you can set

// this number as high as you wish so long as it doesn't impact the user experience.

ctx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(context.Background(), 120 * time.Second)

defer cancel()

// Resume an ongoing update operation (this may terminate the application as

// part of the upgrade process).

err := mgr.Continue(ctx)

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("Unable to apply updates: %s", err)

}

/* --- Your application code would run here --- */

log.Println("Foo Bar!")

// When you decide to perform an update

updateToLatest(ctx, &mgr)

}

// Update to latest will select the most recent update for your application

// and apply it by calling mgr.Update().

func updateToLatest(ctx context.Context, mgr *update.Manager) {

rs, err := mgr.Source.Releases()

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("Unable to fetch the list of available updates", err)

}

availableUpdate := update.LatestUpdate(rs, version)

if availableUpdate != nil {

log.Infof("Update available: %s", availableUpdate.ID)

err := mgr.Update(ctx, availableUpdate)

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("Unable to start update: %s", err)

}

} else {

log.Infof("No updates available")

}

}

Closing

I hope this proves to be a useful dive into how one would go about updating an application in-place and that the example implementation in update-go serves as a starting point for writing your own. In an age where tools like Docker, Kubernetes, Packer and "the Cloud" make deployment processes obscenely complex and magically easy at the same time; sometimes it's nice to play around with something simpler.

I'm using this approach and update-go itself to provide automated updates for git-tool, a developer productivity tool I've been working on to save me the hassle of managing my git repositories. If you're interested in what that looks like, please have a look at the GitHub page.